A note (Latin

nota)

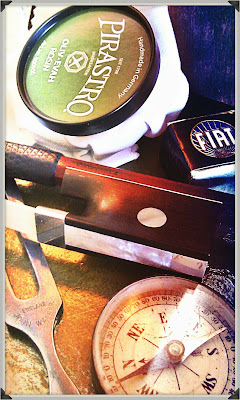

is a written mark used to represent a sound, letter, word, or action. It is also the sign that something has been

noticed, marked, indicated, noted (Latin

notāre). The score from which I play is a palimpsest

of notations, layer upon layer of notes, in ink, pencil, memory, and

imagination. There are the musical notes

Bach must have written, nigh perfectly transcribed by his wife Anna Magdalena

Bach and by Johann Peter Kellner in the two most authoritative manuscripts of

the four that editors collate to arrive at a text of the suites. (They also use a fifth, an arrangement of the

fifth suite for the lute in Bach’s own hand.)

There is the less consistently recorded order of notation in those

manuscripts that may tell us what articulation Bach expected, though we can

argue about how constraining he would in any case have expected his slurs and staccato

marks to be. There are the

ornaments: signs in shorthand which the

player expands into a trill, turn, or shake.

In some of his other compositions Bach gives us more of these than we

have here, so there is again a possible gap between what we find on paper and

what we may imagine were his expectations.

All these manuscript notes authorise even as they are replaced by the

printed notes of the edition – in my case the superb Peters viola transcription

of Simon Rowland-Jones. And there they

are inevitably joined by editorial notes:

the suggested trills in square brackets, the slurs added for

consistency’s sake with lines through them so we know they are not original,

the hypothetical arpeggiation of the bare five chords at the end of the prelude

to the second suite.

Still, fewer notes than in the Watson Forbes transcription from

which I first learned this music, with its suggested tempo markings and dynamics

and its fingerings (the one, and crucial, editorial intervention that Forbes

does not think to mention in his preface).

Many of us may still be haunted by those notes, which lead the player to

a performance very much of the early 1950s, when Forbes published his version –

keeping string crossings and open strings to a minimum, so the sound can be

smooth and intense. My copy includes the

pencil annotations of many younger versions of me (starting at age 11 or so)

and those of my teachers, first Douglas Reid and then Eta Cohen: fingerings, bowings, dynamics, passages to

push the tempo on and moments to hold it back, and more general technical

instructions (from Eta especially) – ‘Finger action at heel’; ‘Steady

practice’. It has been a relief to put

this copy away and work from a clean copy of Rowland-Jones’s edition.

The wonderful 2012 film ‘A Late Quartet’ depicts a string

quartet trapped by the roles their music has cast them in – the first violin, primus inter pares, the cello who is the

base on which the whole is built, the very dependent second violin and viola,

married and squabbling. They play from

parts in which every nuance of interpretation has been fixed in the detailed

pencil annotations they have established over the years, restricting their

movements like arthritic callus. And

they wonder whether they dare play without the notes. Playing from memory is a strange thing, and

one I have become worse at over the years with the day job making its own

demands on my brain function. You

remember the sound of the notes, but that is not enough. You have a spatial sense of the piece, which

for some of us may coincide more or less with a mental picture of the pages of

music. Most of all, you have muscle

memory – your fingers know where they are going before your mind can think it,

much less send an instruction. These

different kinds of memory are less free than you might think from the

film. Muscle memory requires that one

establish a fingering for the music and stick to it rigidly.

How many notes to add to the notes in my still clean

Rowland-Jones edition, then? Should I

work out all the fingerings and bowings and ornaments and dynamics, or should I

leave as much as possible to chance, or rather to the inspiration of the

moment? Ornaments should sound, and be,

spontaneous, but if one doesn’t at least practice possibilities, one can end up

tying the fingers in knots and messing up badly. My compromise is to work my way towards an

outline interpretation, with habitual fingerings and bowings decided (or

alternatives clearly enough in mind to offer a safe choice in the moment of

performance), with the chiaroscuro of varied articulation, ornamentation, and

dynamic in repeated sections thought through (and again, alternatives at least

mentally noted), but to write down as little of this as possible. Because sometimes forgetting is an important

creative tool, and this way I am free to do things differently next time. There are risks to this

approach, but I am still finding my way.